CRER calls for policymakers at local and national levels to develop targeted measures for tackling racialised poverty in Scotland, recognising that current policy approaches are widening racial inequalities.

Ethnicity and Socio-economic Deprivation in Scotland

The Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights (CRER) has published new research on socio-economic deprivation in Scotland, revealing a stark disparity between Black and minority ethnic groups and their white Scottish/British counterparts in terms of their access to economic and social resources. Using the latest population data from Scotland's 2022 Census, CRER's analysis highlights that Black and minority ethnic communities in Scotland are disproportionately concentrated in the most deprived areas and that this inequality has widened over the past decade.

Structural racism contributes to Black and minority ethnic people experiencing a wide range of barriers and disadvantages in their everyday lives, affecting their health, education, employment, access to housing and experiences of crime and the justice sector.

These barriers are often interconnected, meaning that a disparity experienced in one aspect of life can contribute to the broader inequalities someone faces. As a result, they shape someone’s socio-economic status, which can influence their access to opportunities and resources and affect their overall well-being and quality of life.

For instance, people experiencing socio-economic disadvantage are more likely to have poorer outcomes in their work, health, living standards, participation in public life and their interactions with the justice sector.

In Scotland, we typically measure socio-economic disadvantage using a framework called the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation, or the SIMD.

The SIMD is an area-based measure which splits Scotland into 6,976 small areas of approximately equal population and ranks them from the most deprived to the least deprived. The ranking is based on a relative calculation of 30 unique indicators, which include measures for income, employment, education, health, access to services, crime and housing.

Scottish Government figure explaining the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) 2020v2 - learn more

In this context, ‘deprived’ does not solely refer to having ‘low income’ but indicates a greater likelihood of experiencing structural disadvantage across several key aspects of life.

Therefore, if someone lives in an area of high deprivation, it does not necessarily mean that they are personally experiencing high levels of deprivation but indicates that they are more likely to face disadvantage than someone living in a less deprived area.

But how is this deprivation experienced at a community level? Do some groups in Scotland have a greater likelihood of experiencing socio-economic deprivation than others?

To answer this, the Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights (CRER) investigated the links between ethnicity and socio-economic deprivation in Scotland.

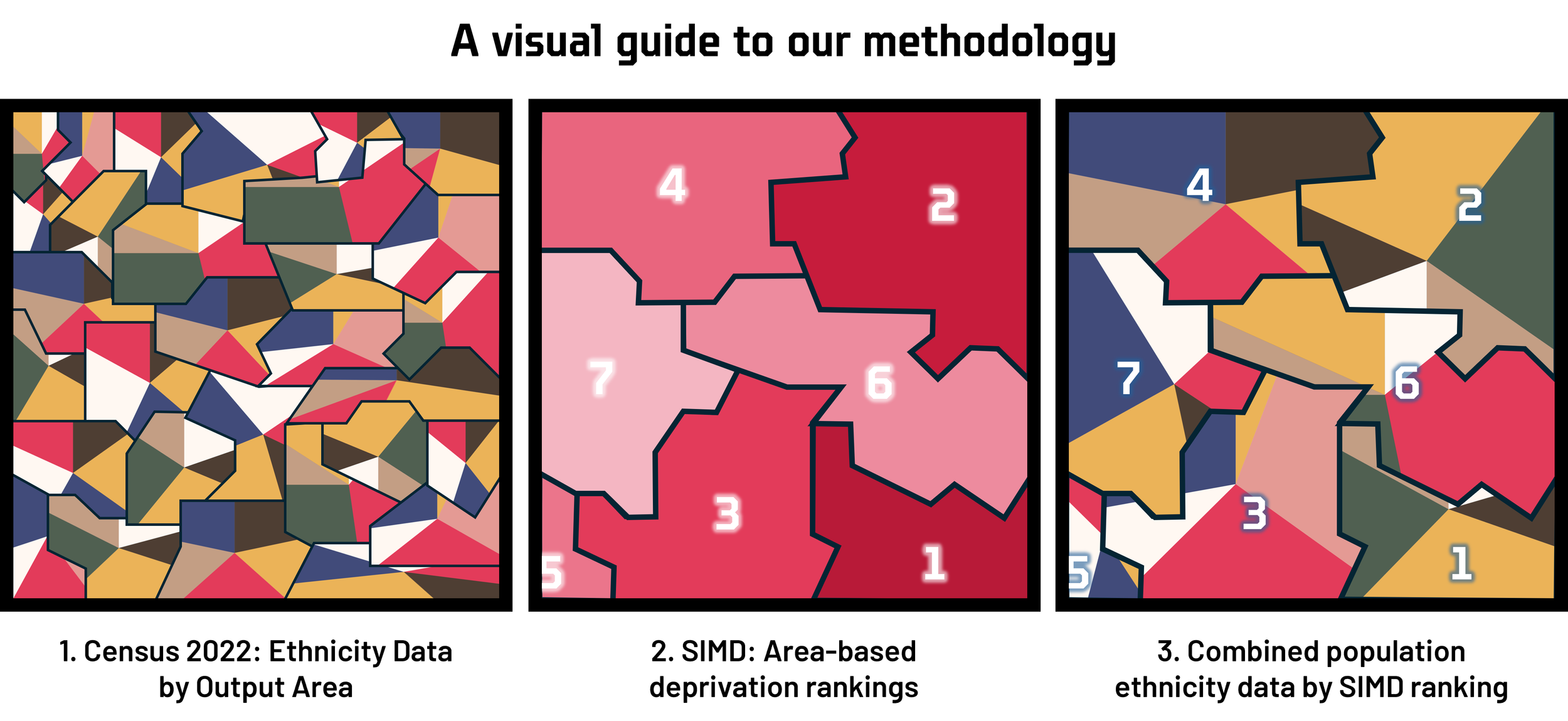

Overview of methods

The 2022 Census serves as Scotland's most recent and comprehensive source of population data by ethnicity. The Census splits Scotland into over 45,000 small areas known as Output Areas, each capturing the number and characteristics of everyone residing there as of March 20th 2022. In contrast, the SIMD divides Scotland into nearly 7,000 Data Zones, ranked by their relative deprivation.

To match ethnicity data with the SIMD, CRER joined data from each Output Area to their corresponding Data Zone and counted the total population of each ethnic group living within its boundaries.

Typically, when the SIMD is used for analysis, these zones are grouped into deciles (10% splits) or quintiles (20% splits) to show how their levels of deprivation generally rank compared to the rest of Scotland. So, if someone lives in the most deprived decile, their local area ranks in the top 10% of Scotland in terms of socio-economic deprivation.

Using these rankings and Census population data, CRER was able to measure the proportion of each ethnic group living in every decile of the SIMD.

This process was first conducted for the whole population and then repeated using population data for those under the age of 16.

For regional analysis, CRER categorised SIMD data zones by their corresponding city, local authority and urban-rural classification and re-ranked their deprivation relative to their unique geographical context. For instance, to determine the dynamics of ethnicity and deprivation in and around Aberdeen, we isolated all data zones located within the Aberdeen travel-to-work area and used their SIMD rankings to produce new, locally-adjusted quintiles of socio-economic deprivation.

What we found

Black and minority ethnic people are 60% more likely to live in the most deprived parts of Scotland than their white Scottish/British counterparts.

CRER’s analysis found significant differences in how the population is distributed across areas of socio-economic deprivation.

African and Arab groups were more than twice as likely to live in the most deprived quintile of Scotland than their white Scottish/British counterparts. In contrast, the proportion of mixed and Indian groups living in deprived areas was much more similar to those from a white ethnic background.

When accounting for Black and minority ethnic groups collectively, we found that a quarter of Scotland’s BME population lived in the most deprived 20% of the country.

When looking at the top 10% of deprived areas, these inequalities become even starker.

Our analysis found that BME groups were 60% more likely to live in the most deprived decile of the SIMD than their white Scottish/British counterparts. In comparison, white minority ethnic groups, such as people of Irish, Polish or Gypsy/Traveller heritage, were 20% more likely than their white Scottish/British counterparts to live in the top 10% of most deprived areas.

Again, African and Arab groups were much more likely to live in the most deprived decile than all other ethnicities, with African groups being over three times as likely to live in the most deprived decile than white Scots/Brits and Arab groups 2.5 times as likely.

People of Bangladeshi, Caribbean or Black, and Pakistani heritage were also more likely to live in the most deprived decile than their white counterparts.

Children from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds are even more likely to live in Scotland’s most deprived areas.

Analysis by CRER found that 30% of Black and minority ethnic children in Scotland live in the most deprived quintile of the SIMD, with African, Arab and Caribbean or Black groups being the most likely to live in socio-economically deprived areas.

For white minority ethnic groups, a similar pattern emerges, as 28% of white minority ethnic children live in the most deprived quintile compared to less than 20% of white Scottish/British children. This is particularly driven by the high proportion of white Polish and Gypsy/Traveller children living in the most deprived parts of Scotland.

Once again, when looking at the most deprived decile of Scotland, Black and minority ethnic children continue to be the most exposed to socio-economic deprivation.

17% of BME children live in the most deprived 10% of Scotland, with this rising to 32% of African children, 26% of Arab children and 21% of children from Caribbean or Black backgrounds.

This echoes wider evidence about child poverty in Scotland, such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Poverty in Scotland 2024 report, which found that 53% of Black and minority ethnic children live in relative poverty – more than double the average rate in Scotland.

How has this changed over time?

As of 2022, Black and minority ethnic people are more likely to live in deprived areas than they were in 2011.

Using population data from Scotland’s previous Census in 2011, we can see how the dynamics of ethnicity and socio-economic deprivation have shifted over time.

For instance, in 2011, just 12% of the Arab population lived in the most deprived parts of Scotland, but in 2022, this rose to 22%. Similarly, the share of Bangladeshi people living in the most deprived 10% of Scotland increased from 8% to 14% between Censuses.

Overall, the gap between white Scottish/British groups and their Black and minority ethnic counterparts has widened over the past 11 years.

We should emphasise that our estimates presented here both rely on deprivation rankings generated through the SIMD2020v2, which was designed from 2011 Census data. As a result, our 2022 analysis serves as a best-fit estimate until a revised Index is developed.

How does this vary across Scotland?

Most BME groups are over-represented in the most deprived parts of Scottish cities.

These inequalities persist across Scotland and its population centres. For instance, regional analysis using both national and localised rankings of deprivation suggests that BME people continue to disproportionately experience deprivation in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen.

However, when looking at individual ethnic groups and their distribution across Scottish cities, the pattern becomes more complicated.

In some cases, specific ethnic groups were consistently over-represented in the most deprived parts of Scottish cities. Other groups were disproportionately exposed to deprivation in one city but not another, highlighting the complexities of racialised poverty and structural disadvantage.

In Glasgow, for example, people of Pakistani heritage were less likely to live in the most deprived quintile than their white Scottish/British counterparts, but the opposite was true for Edinburgh and Aberdeen. Similarly, people of Indian heritage were less likely to live in the most deprived quintile of Glasgow than white Scottish/British people but were more likely to live in the most deprived parts of Aberdeen.

CRER also analysed how the distribution of people in deprived areas varied across Scotland’s local authorities and the rural-urban divide. However, as 90% of Quintile 1 data zones (i.e., areas in the top 20% of deprivation) are urban areas and the vast majority of Black and minority ethnic people live in urban areas, our methods were less well suited for non-urban analysis.

This limitation has been recognised by Scottish Government, which acknowledges that the SIMD is better suited to the analysis of urban deprivation. Future research on the influence of structural racism on BME people’s experiences of rural poverty in Scotland should seek a more suitable methodology than population distribution-based analysis.

Do communities experience the same types of deprivation?

When ranking deprivation in Scotland, the SIMD considers inequalities faced in income, employment, health, education, access to services, crime and housing. These factors – known as domains – can be individually ranked within the SIMD to determine which areas are the most deprived in terms of their housing, local employment rates or access to services, etc.

Using similar methods of analysis, CRER was able to determine the proportion of each ethnic group living in the most deprived quintile for each domain, allowing us to estimate which aspects of deprivation affect Black and minority ethnic groups most.

There are clear priority areas for tackling Black and minority ethnic communities’ experiences of deprivation.

We found that, on aggregate, BME groups were particularly over-represented in the most deprived areas for housing, crime and health but were under-represented in areas with the lowest access to services, most likely because of their concentration in urban areas. For example, African groups were more than three times as likely to live in the most deprived quintile for housing than their expected rate but were less than half as likely to live in the most deprived quintile for access to services.

This echoes wider evidence from Scotland, which shows that high levels of over-crowding and an over-representation in the private rental sector disproportionately expose BME households to poor housing conditions and higher costs.

Some aspects of deprivation affect specific ethnic groups more than others.

Analysis shows that 40% of Scotland’s African, Caribbean and Black population live in the most deprived quintile for income, employment, health, education, crime and housing, but for Indian and Chinese groups, this was only true for housing. In fact, Indian and Chinese groups were under-represented in the most deprived quintile for all domains but crime and housing.

This does not mean that people from Indian or Chinese backgrounds do not face structural disadvantages or discrimination across these aspects of life, as the inequalities they face have been widely evidenced in statistical analysis and social research. However, it indicates that the areas they are most likely to live in do not exacerbate their experiences of inequality to the same extent as other minority ethnic groups, such as African, Caribbean and Black groups and those from Arab backgrounds.

This highlights a clear opportunity for further research to unpack the unique drivers and impacts of deprivation for specific minority ethnic communities across Scotland. There is no universal experience of socio-economic deprivation, and this must also be reflected more strongly in policy and research approaches to tackling structural inequality in Scotland.

So, what does this tell us?

Using the most accurate and recent population data available, our analysis clearly demonstrates that Black and minority ethnic people in Scotland are more likely to experience socio-economic deprivation than their white Scottish/British counterparts.

This inequality has only worsened with time. Since 2011, the proportion of the Black and minority ethnic population living in Scotland’s most deprived areas has increased, and the divide between BME groups and white Scottish/British people has widened.

Despite these inequalities, policymakers continue to overlook the disproportionate effects of poverty and deprivation on Black and minority ethnic groups in Scotland. Without targeted policy interventions to address racialised poverty, local and national anti-poverty measures will continue to fall short of BME households’ and families’ needs.

CRER’s analysis also shows that, based on the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation, some communities are more likely to face significant structural disadvantages than others. For instance, African and Arab groups are more likely to live in deprived areas than other minority ethnic groups and twice as likely than their white counterparts.

Despite this, many of Scotland’s official statistics, including our national measures of poverty, continue to rely on high-level, aggregated ethnicity categories, which mask variations between minority ethnic groups. This perpetuates the notion that minority ethnic groups are a monolith and can downplay the most severe inequalities between them. As a result, it is harder to design and deliver targeted policy interventions for those in the most need.

CRER calls for Scottish Government and other stakeholders to disaggregate all official statistics by ethnicity, in line with the categories used by Scotland’s Census 2022.

Given that the SIMD accounts for income, employment, education, health, access to services, crime and housing, the disparate concentration of BME groups in deprived areas highlights the need for policy change across every aspect of civic life in Scotland. This is especially true for housing inequality, which has been seen to disproportionately affect all minority ethnic groups in Scotland. This can have significant knock-on effects on every part of someone’s life, including their physical and mental health.

Until local and national government prioritises tackling structural racism, they will continue to fall short of their missions to tackle poverty, reduce inequality and promote equality of opportunity.

Scotland can no longer ignore the clear evidence of widening inequality and racialised deprivation demonstrated by CRER’s research. Government and the wider public sector must work collectively to close the gap in the experiences and life chances of Black and minority ethnic people and their white Scottish/British counterparts.

Further reading:

CRER (2024), Challenge Poverty Week: Black and minority ethnic poverty, what you need to know.

CRER (2021), Poverty and Ethnicity in Scotland: Analysis and reflection on the impact of COVID-19.

CRER (2020), Minority Ethnic Communities and Housing in Scotland – Room for Improvement?

CRER (2013), Perceptions on ethnicity, recession and austerity in three Glasgow communities.