Ten Things We Need to Say about Racism

Racism in Scotland is structural. This means it operates across different levels of life - personal, social and institutional. Because of this, the impact of racism affects people across their life experiences. It affects working life, family life, friendships and physical and mental health. Racism is unjust, and should have no place in Scotland.

It’s up to all of us to tackle it. But first, we need to understand its impacts.

3,145 charges were reported in 2022-23, which is more than 8 charges being made per day on average. This is significantly higher than the number of all other forms of hate crime combined, despite known issues with underreporting.

Almost a third of minority ethnic respondents to the 2023 Glasgow Household Survey were concerned about hate crime or harassment due to ethnic origin, race or nationality (compared with 3% of white respondents).

BME communities face varying levels of health inequalities. People from Black African, Caribbean and South Asian backgrounds are at disproportionate risk of developing type 2 diabetes due to a combination of biological, socio-economic and lifestyle factors, including racial inequalities and racism. Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities experience a range of poorer health outcomes including barriers when accessing health services, a higher suicide rate than the general population and poorer mental health linked to poverty.

Racial inequality in healthcare result in Black women being nearly four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women in the UK. Women from Asian ethnic backgrounds are two times more likely to die in childbirth compared with white women.

Alongside this, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Scottish data consistently showed an increased risk of serious illness and death from COVID-19 among many minority ethnic groups.

BME communities disproportionately experience poor mental health due to an increased likelihood of exposure to poverty, adverse life experiences and discrimination. They are more likely to receive lower quality and less effective mental health support in Scotland due to institutional racism. They may also endure racial trauma due to experiencing or witnessing racism, which is largely unrecognised in the Scottish healthcare sector. This means that mental health services are often unresponsive to the needs of minority ethnic people.

Despite these outcomes, weaknesses in ethnicity monitoring of health inequalities within Scotland have been long-established. In recent years, this has begun to shift, with progress on equalities data collection and analysis. This is essential to generate the understanding needed to tackle racialised health inequalities.

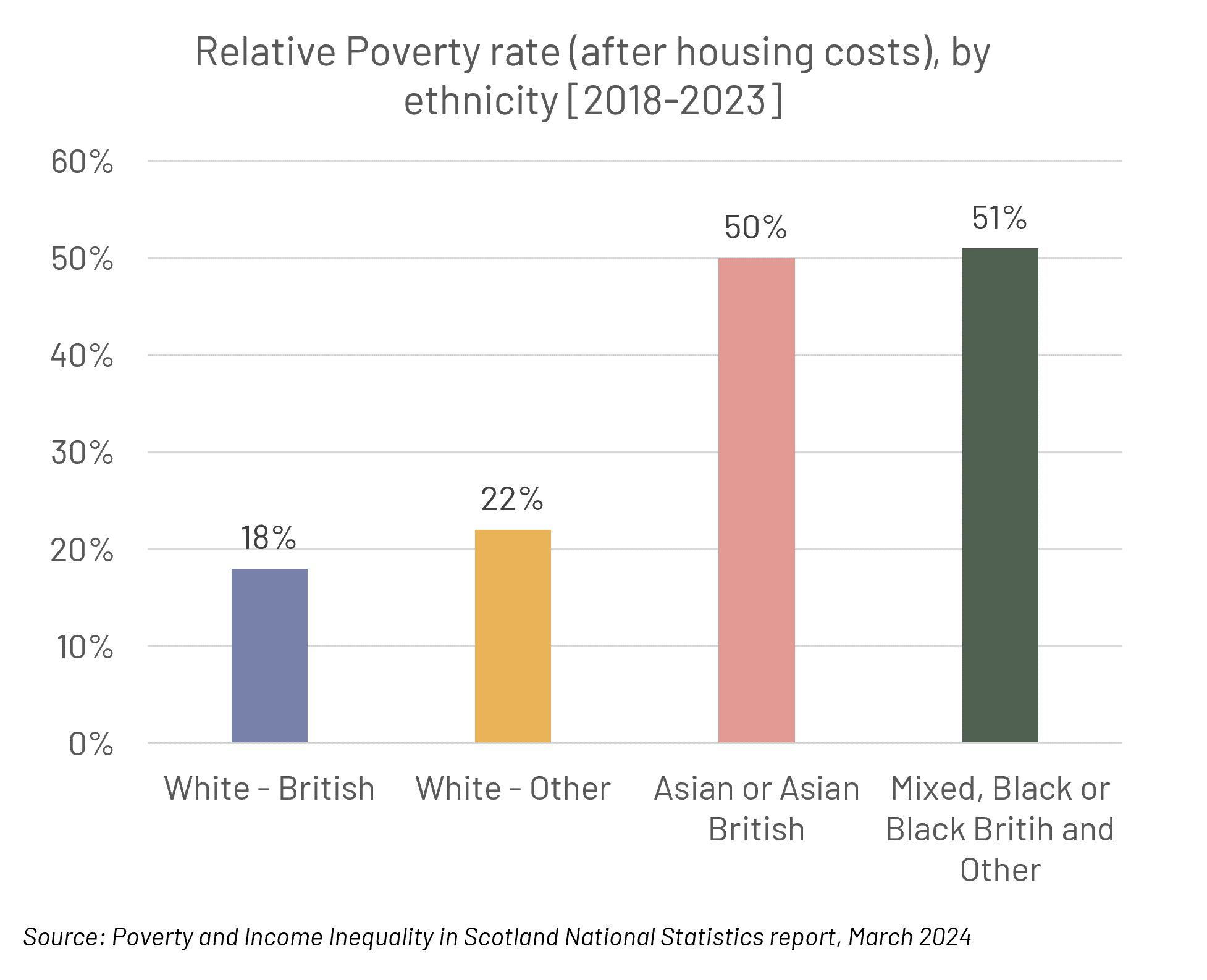

The most recent statistics from 2018-23 show that, both before and after housing costs, the rate of relative poverty in Scotland was more than double for those from BME groups compared to the majority ethnic white Scottish/British group. The poverty rate was 50% for the ‘Asian or Asian British’ group and 51% for the ‘Mixed, Black or Black British and Other’ group, compared to 18% for the white Scottish/British group. More than one-third of all people from a minority ethnic background are trapped in deep or very deep poverty.

Across all measures, poverty rates for children in BME families are higher than in white families. In 2021, 48% of children from minority ethnic families were living in relative poverty. The unacceptable rise in poverty comes despite the identification of minority ethnic families as a priority group for Scottish Government anti-poverty strategies.

Risk of poverty varies significantly among different BME communities. Poverty rates are significantly worse for some high-level-categories of minority ethnic groups in the higher levels categories, (such as ‘Asian or Asian British’) than others. However, in Scotland, more detailed ethnicity breakdowns of poverty rates are relatively rare. A lack of data for specific communities prevents a nuanced understanding of BME communities’ experiences of - and routes out of – poverty. This leads to less effective anti-poverty strategies.

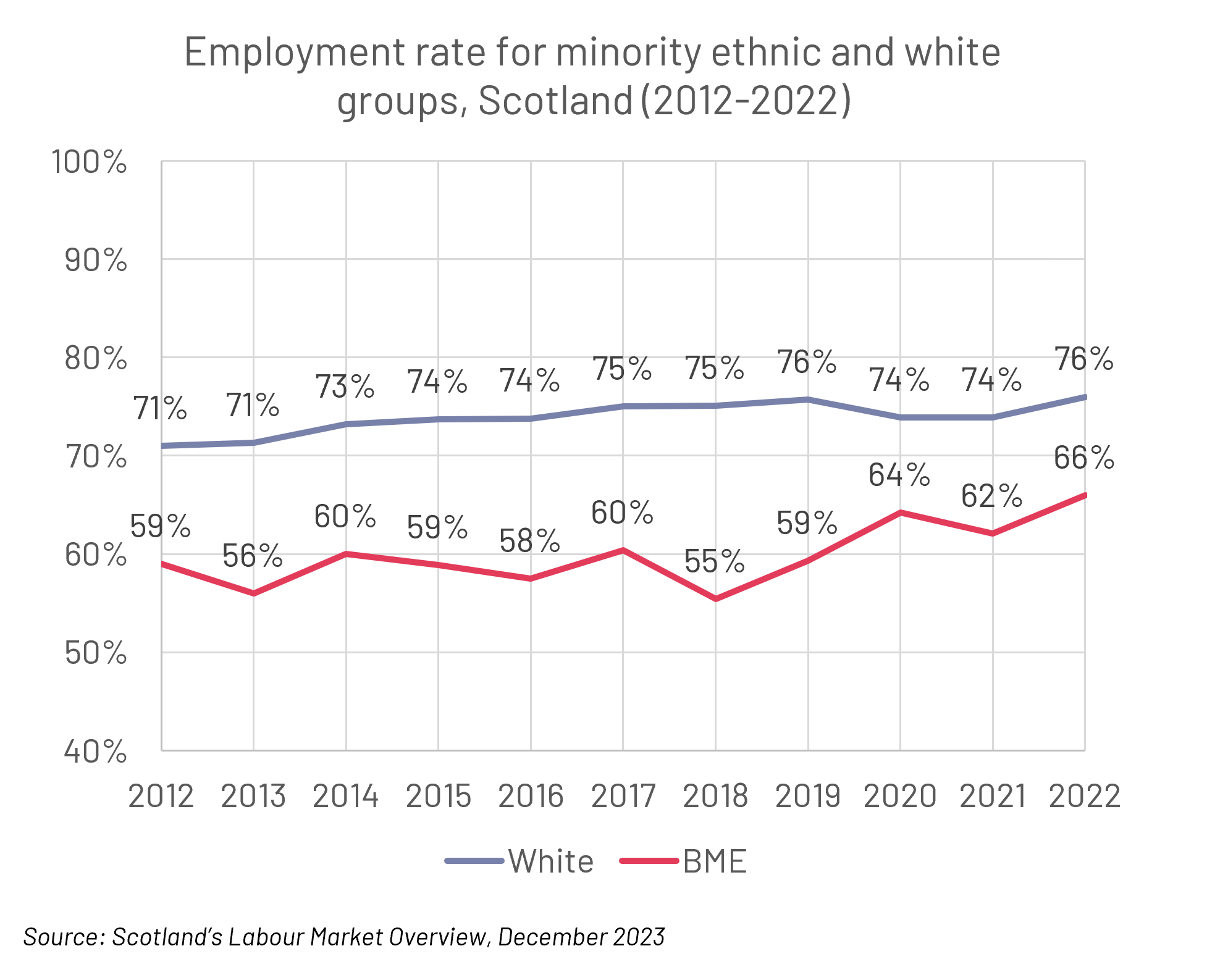

Most white ethnic groups have consistently had an employment rate which far exceeds the BME population, with higher levels of unemployment in certain BME communities. In 2022-23, the gap in employment rates between minority ethnic people and white people in Scotland was 10%.

In employment, BME people continue to be more likely to work in low-paid sectors with little chance of career progression. Linked to this, highly qualified BME individuals can have difficulty securing employment at a level appropriate to their educational qualifications.

BME individuals can face discrimination when applying for a new job or promotion. BME candidates for public sector jobs in Scotland consistently have poorer outcomes. They are less likely to be shortlisted for interview and successfully appointed. Department for Work and Pensions research (which included employers in Scotland) found that a person with a ‘BME name’ had to send an application away 16 times to achieve a successful response compared to the 9 times for someone with a ‘white name’ - even though they were submitting the same application.

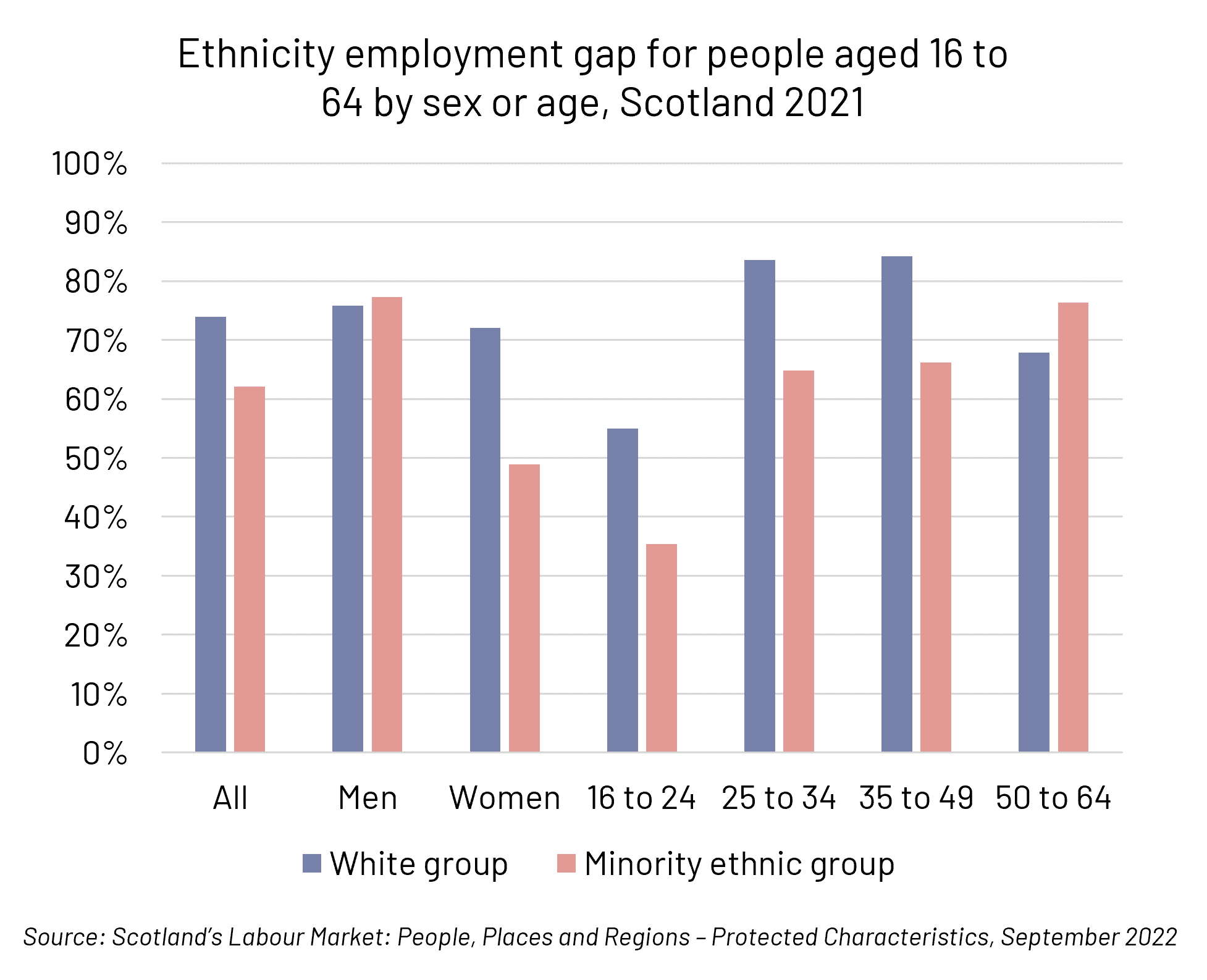

In Scotland, the minority ethnic employment gap is much higher for women than men; in 2021, the ethnicity employment rate gap was around 23% higher for women than men. BME women continue to face serious barriers in access to work, including racist and sexist attitudes and discrimination.

The employment gap is also much wider for young BME people. In 2021, the ethnicity employment rate gap was largest for those aged 16 to 24 at almost 20%, followed by almost 19% for those aged 25 to 34. Contributing to this, graduate unemployment (and under-employment in part-time jobs) is affecting BME graduates in Scotland, who are up to three times more likely to be unemployed compared to white graduates.

Research has highlighted the widespread existence of both subtle, everyday racism and overt racism within schools, impacting BME pupils and BME teachers. Teachers report that bullying based on race is the most frequent type of prejudice-based bullying between learners. Despite lockdown restrictions across the 2020/21 period closing schools at varying points, recording of racially motivated bullying incidents reached its highest level since 2007/08. Over 1,200 incidents were recorded in Scotland’s schools in 2020/21. Whilst this may indicate that reporting levels are improving, the true extent of racism in schools remains unclear due to under-reporting and ineffective recording practices.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission launched an inquiry in 2019 into racial harassment in British universities. The report found that racial harassment is a common experience at universities across the UK, and that it could have a profound impact on an individual’s mental health, educational outcomes and career. Following this, a 2020 report into experiences of BME students at Glasgow University found that over half had been victims of racial harassment on campus. Dundee University’s 2021 survey on how racism and discriminatory behaviour impacts its staff and student body showed that 24% of BAME students and 24% of BAME staff reported they had witnessed or been the victim of racism.

Research has shown that BME communities are more likely to be renting privately than owning their own home or residing in social housing, leaving these groups at greater risk of poverty, unstable letting and more expensive rents.

Minority ethnic households have a higher likelihood of experiencing overcrowding, and in 2016, the Equality and Human Rights Commission stated that in Scotland, “...if you are born into an ethnic minority family today, you are nearly four times more likely to be in an overcrowded household”. In recent years, overcrowding made BME families more vulnerable to the spread of COVID-19 within the household due to difficulty in social distancing. This is an example of how the interrelationship of structural racism and long-standing inequalities, alongside a failure to tackle these, led to higher risks of death or serious illness for some BME communities.

Homelessness is becoming a significant problem for BME people in Scotland; 11% of homelessness applications in 2022/23 were from minority ethnic individuals. There are also differences in experience of homelessness, for example in 2022/23, BME applicants for homelessness assistance spent longer on average in temporary accommodation than white applicants. BME applicants stayed over 290 days on average in temporary accommodation in comparison to 235 days for white applicants. Applicants from African communities averaged the longest at 336 days.

Scotland’s political institutions are not representative of the communities they serve. For the first 20 years following devolution, only four Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) were from a BME background. 2021 saw the first two female BME MSPs elected, bringing the number of BME MSPs up to six out of 129, or 4.6%. There are still significant gaps in representation, with all eight BME MSPs ever to have served in the Scottish Parliament being from South Asian backgrounds.

CRER analysis estimates that, of the 1,227 councillors elected in Scotland at the last Local Government election in 2022, 31 were from a BME background. Over half of Scottish local authorities had no minority ethnic representation. In Edinburgh, of the 63 councillors, only one was from a BME background.

Representation is also low in other decision-making structures. For example, in 2019, 87% of the top Companies House registered charities in Glasgow had trustee boards with a lower proportion of BME trustees than the BME population of Glasgow.

Looking at representation within particular professions, in 2022, just 1.6% of police officers in Police Scotland identified as BME. This affects how BME communities perceive Police Scotland and safety in the community.

BME teachers made up 1.8% of teachers in Scotland in 2022, whereas BME children made up 10% of the pupil population.

Levels of BME representation have remained relatively low for many years, with a knock-on effect on racial inequalities across many systems and structures. As Scottish society becomes more diverse, this needs to be reflected in the workforce, in politics and in decision making.

Slavery-derived wealth contributed to economic growth across Scotland, especially in cities such as Glasgow and Edinburgh. This wealth was integral to the development of Glasgow City Centre in the 18th and 19th centuries, funding the development of buildings such as the Mitchell Library and the wider urban growth of the city.

Scottish people were overrepresented as beneficiaries of the slavery economy. In 1754, individuals with Scottish surnames owned a quarter of taxable land in Jamaica. The compensation paid out by the British Government to enslavers after the Abolition Act of 1833 shows that Scots got 15% of the money at a time when Scotland had just over 10% of the population of the UK. Ordinary Scottish people were impacted by the transatlantic slavery trade as well. For example, those with jobs in the linen industry, particularly in Dundee, profited from the sale of linen to plantations in the Caribbean and the United States where it was used to clothe enslaved people.

Knowledge about this history is often limited and, in many cases, is not covered in school curriculums. In the 2022 Glasgow Household Survey, 60% of respondents knew either nothing (32%) or not very much (28%) about Glasgow’s connections to transatlantic slavery.

Efforts to redress this lack of knowledge are being undertaken. For example, Scottish universities are undertaking research into the legacies of links to slavery and empire and the ways in which their institutions benefitted from slavery. Glasgow City Council's Slavery Legacy Working Group has also started a conversation on how the city should reckon with streets and monuments dedicated to people who owned or trafficked enslaved people, as well as the wider legacies of slavery and colonialism.

BME people in Scotland are less likely to report having people in their neighbourhood who they could trust to help them. For example, in 2018, 86% of people from a white ethnic group felt that they could count on someone in their neighbourhood to keep an eye on their home, compared to only 67% of minority ethnic people.

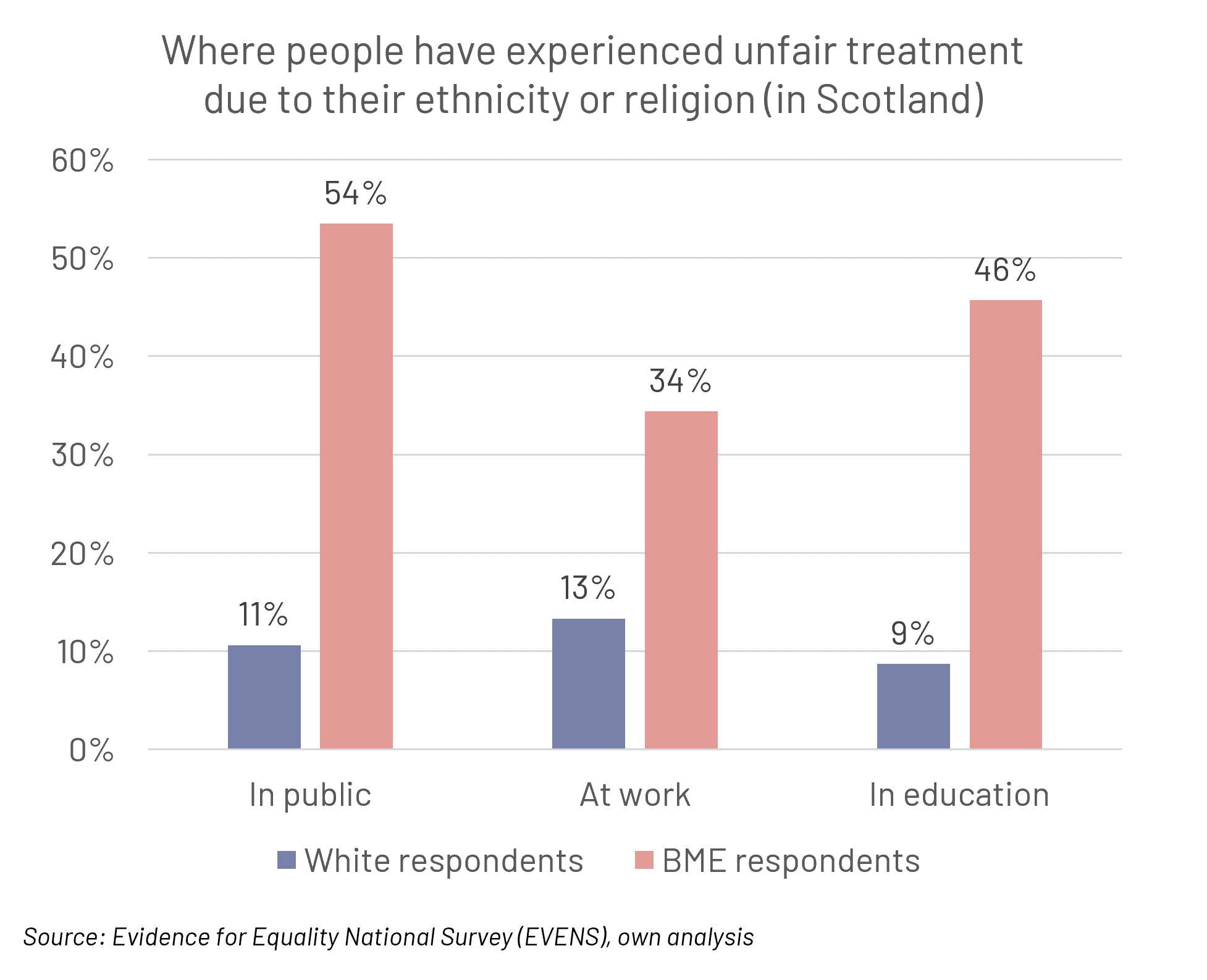

In 2022, 21% of those from a BME group reported experiencing discrimination, compared to 8% of those from a white ethnic group. The presence of overt racial hostility in Scotland is perhaps most seriously highlighted by the presence of far-right groups, with far-right terrorism concerns growing in recent years. The recruiting tactics and propaganda of these groups are reflected in common, everyday messages pushed through both social and mainstream media around threats to safety, economic stability and cultural life.

For more information on what organisations can do to tackle racism and racial inequality: CRER Publications

For more information on what you can do to help: Support our Work